Brain-computer interfaces (BCIs) provide a direct communication link between the brain and a computer or other external device. They provide a high degree of freedom by replacing and augmenting human working capacities, and have tremendous applications in fields as diverse as emotional computing, rehabilitation, gaming, robotics, and neuroscience.

Significant research efforts on a global scale provide common platforms for standardizing Brain-computer interfaces technology, helping to tackle the highly complex and nonlinear dynamics of the brain and the challenges of extracting and classifying relevant features.

Time-varying psycho-neurophysiological fluctuations and their impact on brain signals pose another challenge for BCI researchers to transform this technology from laboratory applications to plug-and-play everyday life.

What is BCI technology?

A BCI, or brain-computer interface, is a computer-based system that is capable of analyzing the brain signals it acquires and converting them into commands that are presented to a device to perform a selected action.

In fact, BCIs do not take advantage of the natural processes of nerves and muscles surrounding the brain. Therefore, BCIs can be limited to systems that measure and use signals generated by the central nervous system (CNS).

For example, a muscle-activated communication system is not a BCI. Furthermore, a device Electroencephalogram (EEG) alone is not a BCI, as it only records brain signals but does not produce any output that affects the user’s environment.

It is a misconception that BCIs are mind-reading devices. Brain-computer interfaces are not meant to extract information from users involuntarily, to read minds, but rather to enable users to act on the environment using brain signals instead of muscles.

In fact, the user and the Brain-computer interfaces work together. The user, often after a training period, produces brain signals that encode the goal, and the BCI, after training, decodes the signals and translates them into commands to an output device that fulfills the user’s goal.

Physiological signals used by BCIs

In principle, any type of brain signal can be used to control a BCI system or brain-computer interfaces. The most commonly studied signals are electrical signals, which are mainly generated by changes in the polarity of the neuronal postsynaptic membrane, which occur due to the activation of voltage-gated or ion channels.

Scalp EEG, first described by Hans Berger in 1929, is a major measure of these signals. Most early BCI work used scalp-recorded EEG signals, which have the advantage of being easy, safe, and inexpensive to acquire.

The main disadvantage of scalp recordings is that the electrical signals are significantly attenuated in the process of passing through the hard tissues, skull, and scalp. Therefore, important information may be lost. The problem is not merely theoretical.

Epileptologists have long known that some seizures that are clearly detectable during intracranial recording are not seen on scalp EEG. Given this potential limitation, recent work on brain-computer interfaces has also explored intracranial recording methods.

Classical computers are really much more sophisticated versions of pocket calculators. They are based on electrical circuits and switches that can be on (one) or off (zero). By stringing together a large number of these ones and zeros, they can store and process any information.

However, their speed is always limited by the fact that large amounts of information require a large number of ones and zeros to represent it. Instead of being simple ones and zeros, quantum computing qubits can exist in many different states.

Signal reception Brain-computer interfaces

Signal acquisition and measurement of brain signals using a specific sensing method (e.g., scalp or intracranial electrodes for electrophysiological activity, fMRI for metabolic activity). The signals are amplified to levels suitable for electronic processing and may also be filtered to remove electrical noise or other undesirable signal features such as 60 Hz power line interference. The signals are then digitized and transmitted to a computer.

The future of brain-computer interfaces

The research and development of brain-computer interfaces is generating tremendous excitement among scientists, engineers, physicians, and the general public. This excitement reflects the rich future of brain-computer interfaces. They may eventually be routinely used to replace or restore useful function to people who are disabled by severe neuromuscular disorders.

They may also improve rehabilitation for people with stroke, head trauma, and other disorders. However, this exciting future can only be realized if researchers and developers of brain-computer interfaces solve problems in three critical areas: signal acquisition hardware, BCI validation and deployment, and reliability.

Signal acquisition hardware

All BCI systems depend on sensors and associated hardware that receive brain signals. Improvements in this hardware are critical to the future of BCIs. Ideally, EEG-based (non-invasive) BCIs should have electrodes that do not require skin abrasion or conductive gel (i.e., so-called dry electrodes).

They must be small and portable. They must be easy to install and aesthetically pleasing, and they must be easy to adjust. They must operate for many hours without maintenance. Brain-computer interfaces must perform well in all environments and easily interface with a wide range of applications.

In principle, many of these needs can be met with current technology, and dry electrode options are becoming available.

Validation and dissemination of brain-computer interfaces

As work progresses and BCIs begin to see real clinical use, two important questions arise: How good can a given brain-computer interface be, and how capable and reliable is it? And which BCI is best for what purposes?

To answer the first question, any promising BCI must be optimized and the limitations of its capabilities identified. Addressing the second question requires consensus among research groups on which programs should be used to compare brain-computer interfaces and how performance should be evaluated.

The most obvious example is the question of whether the performance of BCIs that use intracortical signals is significantly superior to that of BCIs that use ECoG signals or even EEG signals. For many prospective users, invasive BCIs must offer significantly better performance to be preferred to noninvasive BCIs.

Reliability of Brain-computer interfaces

Although the future of BCI technology certainly depends on improvements in signal acquisition and clear validation studies and workable propagation models, these issues pale in comparison to the related reliability problem. In general, regardless of the recording method, signal type, or signal processing algorithm, the reliability of brain-computer interfaces is poor for all but the simplest applications.

Brain-computer interfaces suitable for real-world use must be as reliable as natural muscle-based actions. Without major improvements, the real-world utility of BCIs will be limited, at best, to the most basic communication functions for those with the most severe disabilities.

Conclusion

Many researchers around the world are developing brain-computer interfaces, which were once the realm of science fiction, using various brain signals, recording methods, and signal processing algorithms.

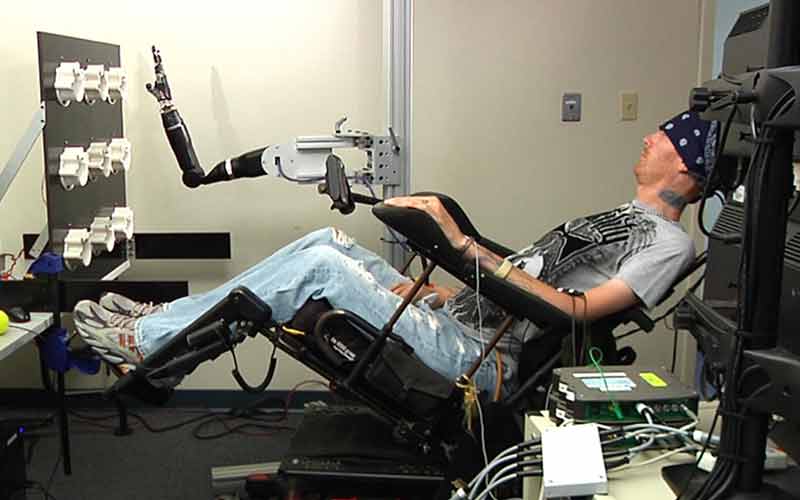

They can operate many different devices, from cursors on a computer screen to wheelchairs and robotic arms. A small number of people with severe disabilities currently use brain-computer interfaces for basic communication and control in their daily lives.

With better signal acquisition hardware, clear clinical validation, workable propagation models, and increased reliability, BCI may become a new communication and control technology for people with disabilities and possibly for the general population.